The solitude of Abkhazia, by Douglas W. Freshfield

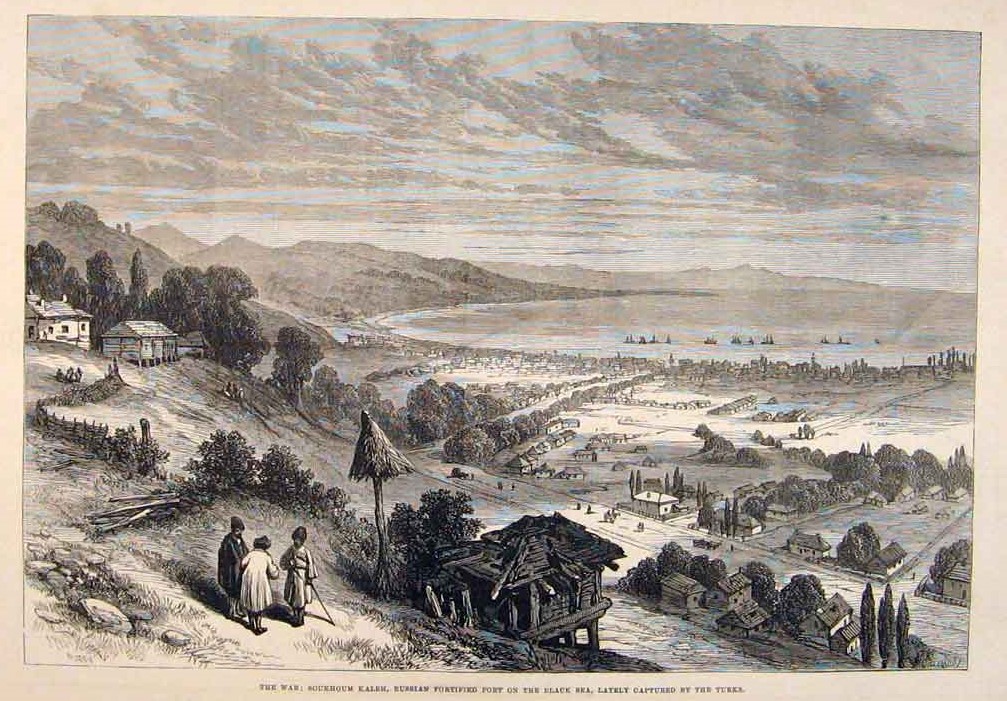

An excerpt from ‘The solitude of Abkhazia’ (pp.191-220), where Douglas W. Freshfield affectionately describes not only the wonderful scenery but also the sad desolation following the migration of the bulk of Abkhazia’s autochthonous population to Ottoman lands following the end of the great Caucasian war (1864) and the Russo-Turkish war (1877-78). The Exploration of the Caucasus Volume II:

"What is to be the future of this Earthly Paradise? Its ancient and primaeval inhabitants are gone. They have been exiled for a quarter of a century; their dwellings and their tombs are alike lost in the glorious vegetation that feeds nothing but bears and mosquitoes and fevers. A people that had lived the same life in the same place since the beginning of history has been dispersed or destroyed. The Abkhasians have vanished, leaving behind them no records, and hardly sufficient material for the ethnologist who desires to ascertain to what branch of the world’s ‘families’ they belonged. Recent Russian writes can add little to the portrait and the epitaph furnished by Gifford Palgrave, who, when Vice-Consul at Sukhum Kale in 1876, was almost a witness of their last struggle. I borrow a page from the chapter on Abkhasia in his Eastern Studies:

“Of the early history of the Abkhasian race little is known, and little was probably to be known. More than two thousand years since we find them in Greek records inhabiting the narrow strip between the mountains and the sea along the central eastern coast of the Euxine, precisely where later records and the maps of our own day place them. But whence these seeming ‘autochthones’ arrived, what the eradle of their infant race, to which of the ‘earth families,’ in German phrase, this little tribe, the highest number of which can never have much exceeded a hundred thousand, belonged, are questions on which the past and the present are alike silent.

Tall stature, fair complexion, light eyes, auburn hair, and a great love for active and athletic sport might seem to assign to them a Northern origin, but an Oriental regularity of feature and a language which, though it bears no discernible affinity to any known dialect, has yet the Semitic postfixes and in guttural richness distances the purest Arabic or Hebrew, would appear to claim for them a different relationship. Their character too, brave, enterprising and commercial in its way, has yet very generally a certain mixture of childish cunning and a total deficiency of organising power, that cement of nations, which removes them from European or even from Turkish resemblance, while it recalls the so-called Semitic of Western Asia. But no traveller in this part lays claim to the solution of their mystery, and records are wanting among a people who have never committed their vocal sounds to writing: they know that they are Abkhasians and nothing more.”(1)

In the future, possibly, the solitude that was once Abkhasia will be repeopled. As yet the Government is lukewarm and unpractical in its efforts. Emigrants, Greek or German, arrive but slowly, and their families too often suffer severely from the fatal fever. There is little in the surroundings, moral or physical, to encourage that energy which tames Nature to human uses. Nature is triumphant; not a virgin Nature, but a Circe who stands ready for all new-comers with a cup of Kolkhian poison in her beautiful hands.